Labor regulators have had their hands full keeping track of all the methods employers use to disavow responsibility for their employees. In a decision issued Monday, the National Labor Relations Board drew a firm line through one maneuver that has hamstrung union organizing in shops that employ “permatemps” and contract workers side by side with direct employees.

The decision affects factories, stores and other workplaces where one firm employs some workers directly, but also contracts with a temp or recruiting firm to fill out the workforce. For more than a decade, a union hoping to organize all those workers into a single bargaining unit had to get permission from each of the employers to do so — the ultimate “user” employer and the contract supplier.

Anyone familiar with the Act’s history might well wonder why employees must obtain the consent of their employers in order to bargain collectively.

The prospect that all such employers would voluntarily agree to allowing their workers to be unionized was “of course laughable,” as labor historian Erik Loomis puts it.

The majority in the 3-1 NLRB vote agreed. “Anyone familiar with the [National Labor Relations] Act’s history might well wonder why employees must obtain the consent of their employers in order to bargain collectively,” the members observed. The answer has much to do with how the law evolved in recent decades. Before we get to that, some context.

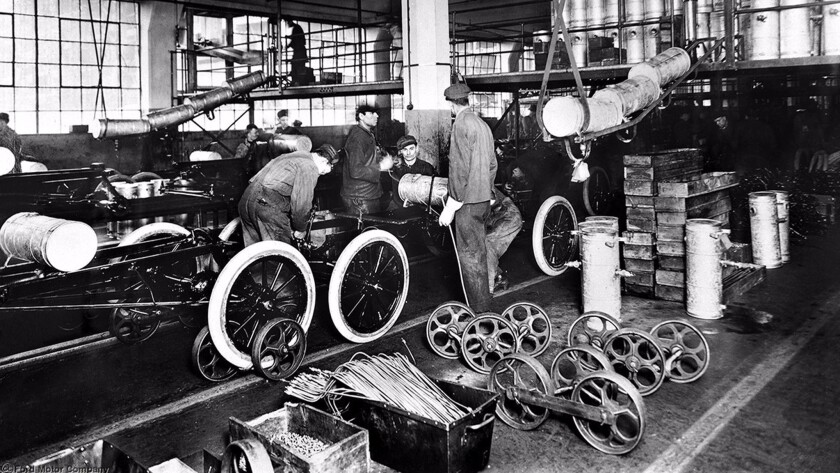

The board has been grappling lately with new forms of employment that undermine the traditional employer-employee relationship prevailing in 1935, when the National Labor Relations Act was enacted. Among them are designating workers as “independent contractors” and thereby sticking them with the cost of equipment, insurance, supplies, and more while depriving them of wage and hour protection and fringe benefits; we can think of this as the Uber model.

Some big employers push responsibility for employees downstream to franchise operators, who can avoid many state and federal labor regulations by claiming to be small businesses as opposed to massive multinationals. This is the McDonald’s model, which is under active attack by the NLRB; the board’s position is that McDonald’s and the franchisees are “joint employers,” so McDonald’s bears legal responsibility. A trial already has been conducted before an administrative law judge, but the smart money in the labor expert community says that McDonald’s is in trouble. But there are numerous procedural hurdles to be cleared before a final ruling is rendered.

The new case, which is dubbed Miller & Anderson after the plumbing and air-conditioning firm at its center, is a close cousin of Browning-Ferris. The issue is whether the overall employer and its worker recruiting firm are separate employers. If they are, then the organizing model must follow the multi-employer rules that apply when a union organizes trade or craft workers in several independent shops.

But what about when workers are employed side by side in a single plant? The NLRB long held that they could unionize as a single unit if they were essentially performing similar work and the main employer effectively controlled their hours, pay and working conditions. The idea was codified in a 2000 ruling known as Sturgis.

The NLRB overruled Sturgis in 2004, under George W. Bush, when it found in a nursing-home case that the nursing home and the staffing agency it brought in to provide some workers were separate employers, and permission was needed from each for a union to organize them.

The NLRB has now scrapped that 2004 ruling, which is known as Oakwood. The board draws a distinction between a genuine multi-employer case, in which the employers are separate businesses that are “often in competition for work with each other, operate at separate locations … and hire their own employees.” In Miller & Anderson, one employer actually works for the other, the workers operate side by side and they’re jointly hired.

It should come as no surprise that the employer lobby is up in arms about all these NLRB initiatives. The board’s lone Republican member, Phillip Miscimarra, asserted in his dissent in Miller & Anderson that Browning-Ferris and the new ruling will “result in confusion and instability” in labor negotiations.

“The activists at the National Labor Relations Board are at it again,” thundered the U.S. Chamber of Commerce after the Miller & Anderson ruling came down. “The activists running the agency appear willing to use any pretense imaginable to overturn precedents and craft lopsided regulations that will help their union allies.” The Chamber agreed with Miscimarra and complained, fairly enough, that the impact of the latest ruling is magnified by the joint employer doctrine underlying Browning-Ferris and the McDonald’s case.

Well, yes, that’s the point.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.